News

BIM Execution Plan and Information Exchange Requirements developed under the same methodology

Around 2006, when I started learning about BIM and trying to implement it in projects, the most glamorous term known at that time was “BIM Execution Plan”. For the small number of Bimners at the time, this document was shrouded in a certain amount of mystery, as there were very few references on how to write it, who was responsible for doing it and, most importantly, what its content should be. Talking about the BEP was like talking about sex in my adolescence. Something that many people talked about, but almost nobody practiced. To give you an idea, at that time Chuck Eastman’s famous “The BIM Handbook” had not yet been published.

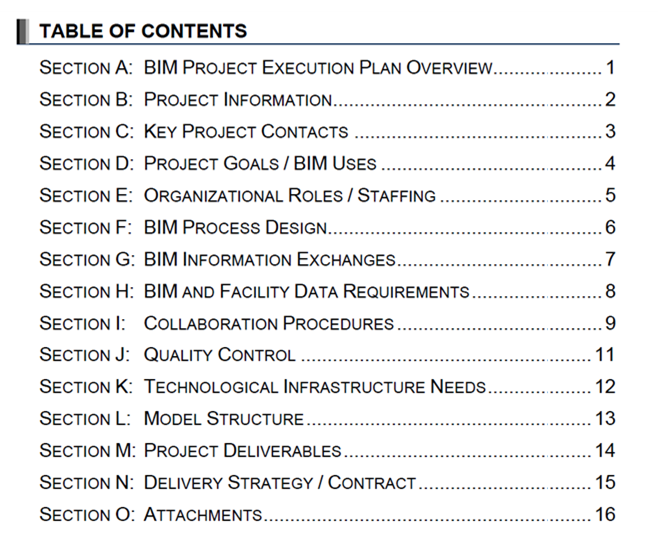

After some time, the University of Pennsylvania published the “Guide for BIM Execution planning”, in which it proposed not only a methodology for BIM planning, but also a template for its drafting.

Obviously, that template served as an inspiration for many professionals, who saw in it a reference for the development of their own BEPs. It was also one of the first clear cases of “Cargo Cult” that I remember, as many of my colleagues were more concerned with diligently filling in the blanks of the template than understanding the meaning of each section and developing their own way of doing, adapted to the context of their requests.

The need to set customer requirements

Meanwhile, contracting parties also began to implement BIM and, and with them came the need to include in the contracting processes other documents as well, detailing how they wanted their suppliers to implement BIM in the project assignments for which they were contracted.

This generated some confusion at the beginning, because the most immediate reaction of many consultants was to use the BEP for this function. This was not very orthodox, as this document made sense as a planning tool and not a requirements specification tool (even at the pre-contract stage, its function remains the same).

In my particular case, I think my first job in this regard was to develop the requirements for the implementation of BIM for the first projects of a well-known soccer club in 2015. At that time, we called it “General Specifications”, but its structure was the same as the BEPs we were already implementing in the first two project assignments for the same client, in which we acted as BIM Managers of the project. This forced us to explain very well to the rest of the suppliers the meaning and use of these two documents: while the first one explained the expectations of the contracting party, the second one specified how these requirements were implemented in the different project assignments managed by the contracting party.

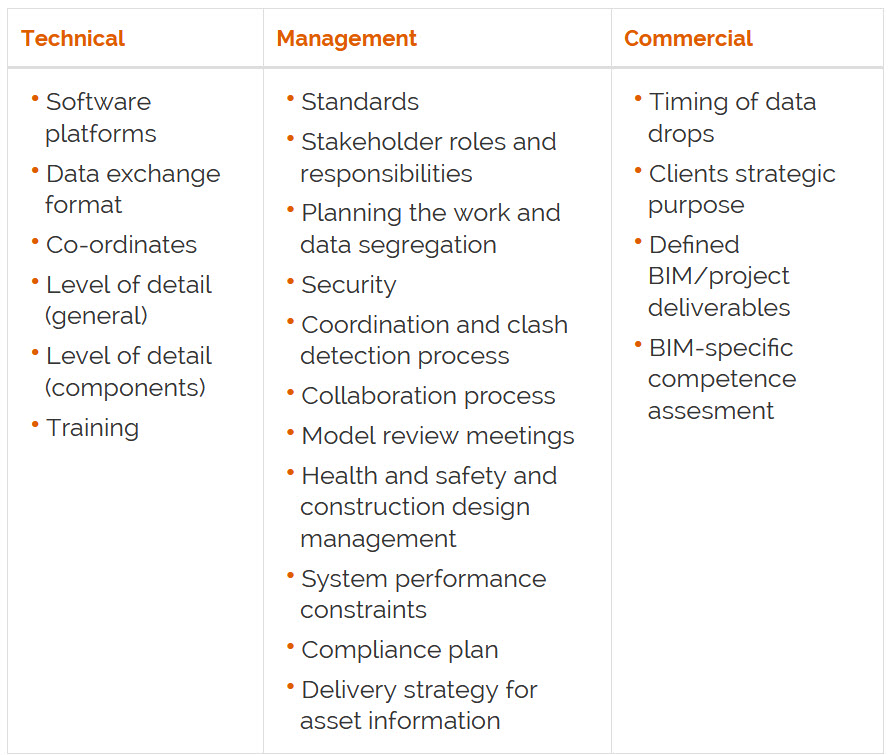

Obviously, the same idea was developed under other names, being the term “Employer Information Requirements” the most widespread at international level, being included in the PAS-1192 published in 2013 by the British Standards Institution. As expected, this became the new reference for many people, establishing that these requirements should be grouped into three sections:

- Information management

- Commercial management.

- Competence assessment.

The version published by the BIM Task Group, which is still available on the Scottish Future Trust website, was also widely disseminated and structures the document in the following sections:

Nowadays this term has evolved into a broader concept called “Exchange Information Requirements”, contained in ISO 19650-1. Although this standard has not yet established the exact content of this document, it does seem to follow the previous approach, stating that the EIR “set out managerial, commercial and technical aspects of producing project information”.

The BEP as a response to the EIR

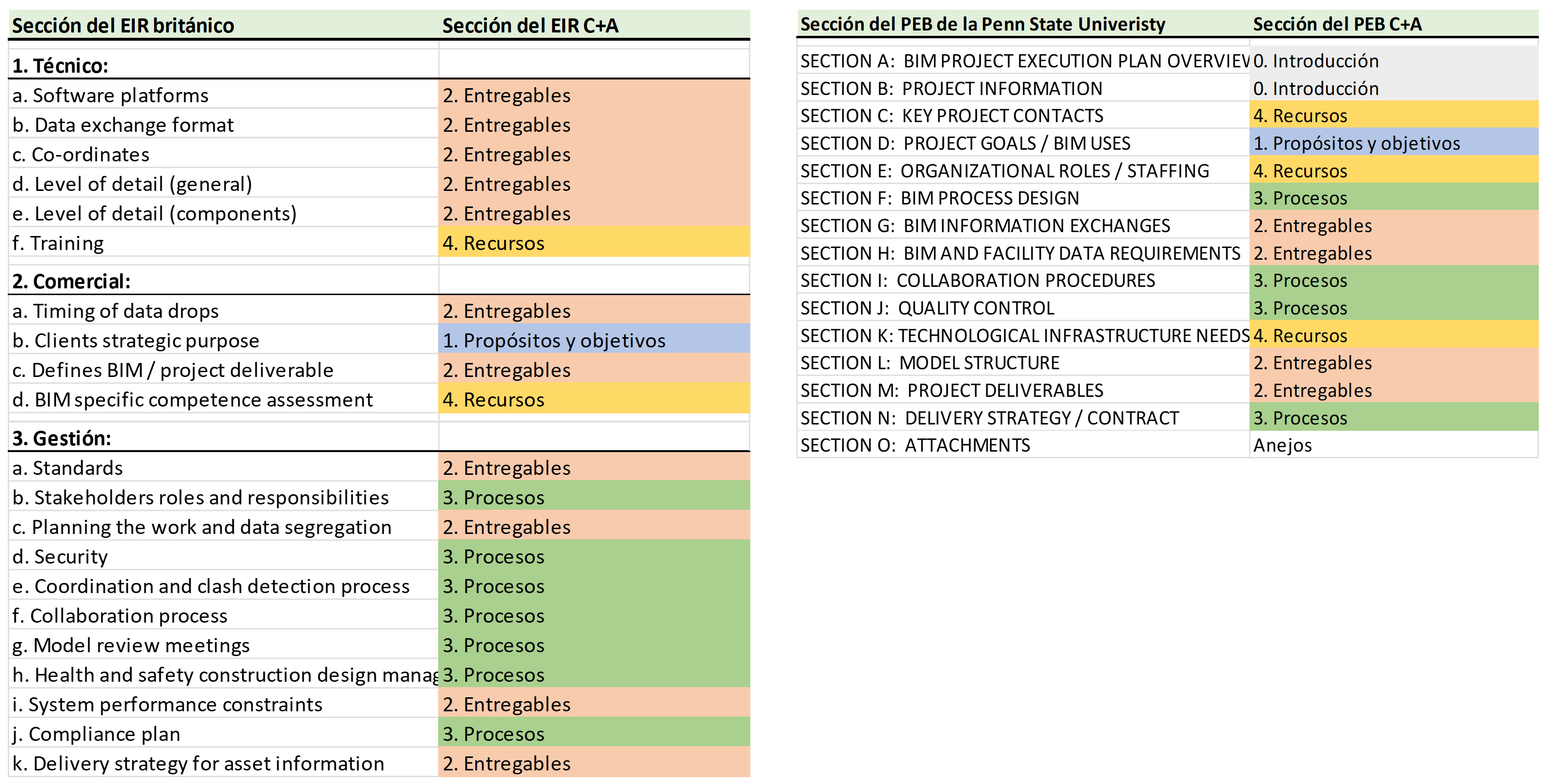

Both PAS and the recent ISO 19650 state that the BEP should describe how the EIRs of the contracting parties will be implemented in a particular project assignment. The problem is that these two international references (Penn State University’s BEP and the EIR in either version) do not have the same structure. Over time, this difference has been increasing, since the different agents that have been generating this type of documents have been developing their own way of doing it according to their needs (as is logical). In fact, only a small part of the EIRs and BEPs that have fallen into my hands follow the schemes described above. Even when an EIR includes a template for writing the BEP, it usually follows a completely different structure.

In my opinion, this represents a drawback, as it makes it difficult for the contracted parties to know which part of the EIR describes each point to be taken into account in the drafting of the BEP. It should be borne in mind that not all EIRs describe everything necessary or with sufficient specificity, so the engagement development team has no choice but to do a comparative analysis in order to avoid omissions and to clearly identify the gaps in the EIR that need to be addressed during the drafting of the BEP.

Contracting parties also suffer the consequences of structuring the EIR and BEP differently, as they must review the correspondence of what is described in the BEP with what is required in their EIR, although it is true that if they themselves are the authors of the BEP template to be used by the contracting parties it will be easier for them.

On the other hand, it should be borne in mind as well, that there will not always be only one contracting party bringing its EIR to the table, as ISO contemplates, EIRs can be multiple, either because they are aggregated (several agents at the same contracting level) or chained (subcontracting). In fact, strictly speaking, since ISO 19650 concerns only information management (“Appointed party: provider of information concerning works, goods or services”), it could be interpreted that service providers should also contribute their respective EIRs to the BEP drafting process, since they will sometimes be the ones requesting information from their contract partners or even from their clients.

Therefore, it seems that the most practical approach would be for the EIR and BEP to share the same structure to facilitate the traceability of the correspondence between the two.

But then, what should be the structure of these documents? Is it possible to organize their content under the same structure? Is it possible to standardize their content at least up to a certain level, in order to make it easier to integrate the various EIRs of the agents involved in a project assignment?

The EIR and the BEP as a description of a work methodology

It has always been said that BIM is a working methodology. Therefore, it seems logical to describe its implementation as from this perspective. According to the dictionary, a methodology is the application of a procedure for a specific purpose. This fits very well with an idea that for us is fundamental, that the use of BIM has a goal. Moreover, as we will see later, it must also have a purpose.

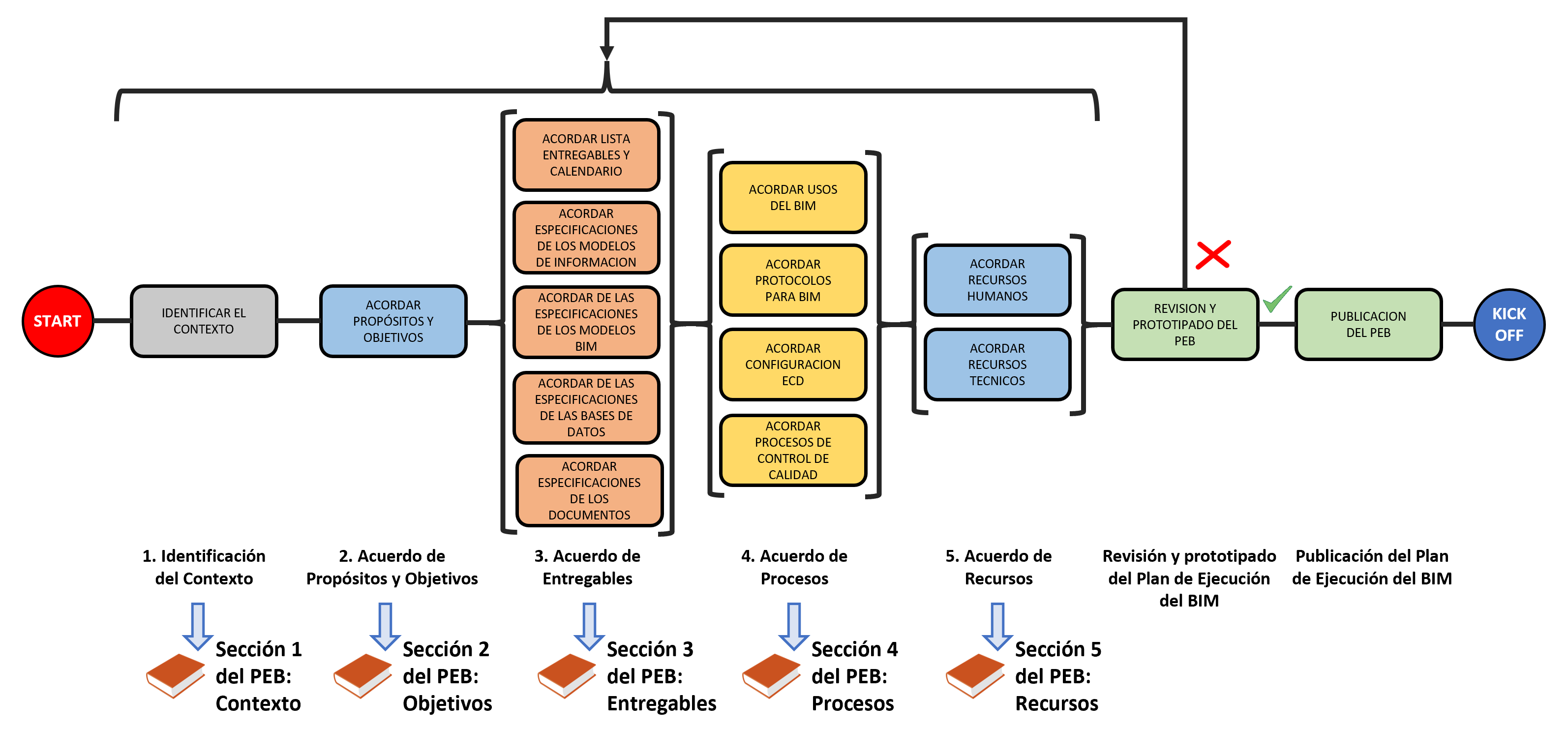

From this point on, it would be logical to describe this methodology in the following steps:

1. Describe the Context

Whether it is the requirements of the stakeholders involved in the project assignment (EIR) or the planning of the BIM implementation in the project assignment (BEP), it is important to contextualize it. In other words, describe the background, the scope, the references used, the application standards, etc. We also add contact details in case of queries and a glossary of terms in this section.

2. Describe the Aims and Objectives

It defines Why and What is the purpose of implementing BIM in the project. This part is the most important since it is the one that gives meaning to the use of BIM and it is worth working on it from the beginning. Paradoxically, our experience shows us that this is usually the part that is the least worked on, especially the purpose part. Most of the existing literature speaks only of the need to define objectives (“what for”). Only ISO 19650 makes any direct reference to the need to define purposes “The appointing party should state their purposes for requiring information deliverables” (ISO 19650-1).

3. Describe the Deliverables

What needs to be produced to achieve the objectives defined in the previous section is defined taking into account its purpose and When these exchanges should take place.

4. Describe the Processes

It defines how the deliverables described in the previous step are to be obtained and who participates in each process. Therefore, this chapter includes the uses of BIM applicable to the project assignment, which are justified by obtaining specific deliverables according to certain purposes and objectives. It also includes the description of other processes, such as Initiation and Coordination, or quality control mechanisms.

5. Describe the Resources

Finally, the resources needed to execute the processes described above are defined, in other words, With What. This section includes both technical and human aspects. We are talking about software, but also about the competencies required by the different agents involved in the project assignment.

This structure is compatible with both the main reference for the EIR and its homonym for the BEP, ordering its sections following the process of defining a methodology. In this case, that of implementing BIM in a project assignment.

EIR and BEP development as a decision-making process

The advantage of this approach is that the development of the different parts follows an appropriate order for decision making. It goes from the strategic to the technical, establishing what is to be achieved independently of how it is to be achieved.

Therefore, a drafting process for this type of document can be designed following these 5 steps:

As can be seen, such a process can be used to help a contracting party develop its information requirements, especially when it must serve the needs of different departments within the same organization or to merge requirements from various internal customers.

On the other hand, when this structure is used for the elaboration of the EIR, it is logical to include a template for the drafting of the BEP by the future suppliers. Since the outline is the same, the template can be offered pre-populated with everything contained in the EIR, facilitating its use as a starting point to whoever has to develop the project assignment.

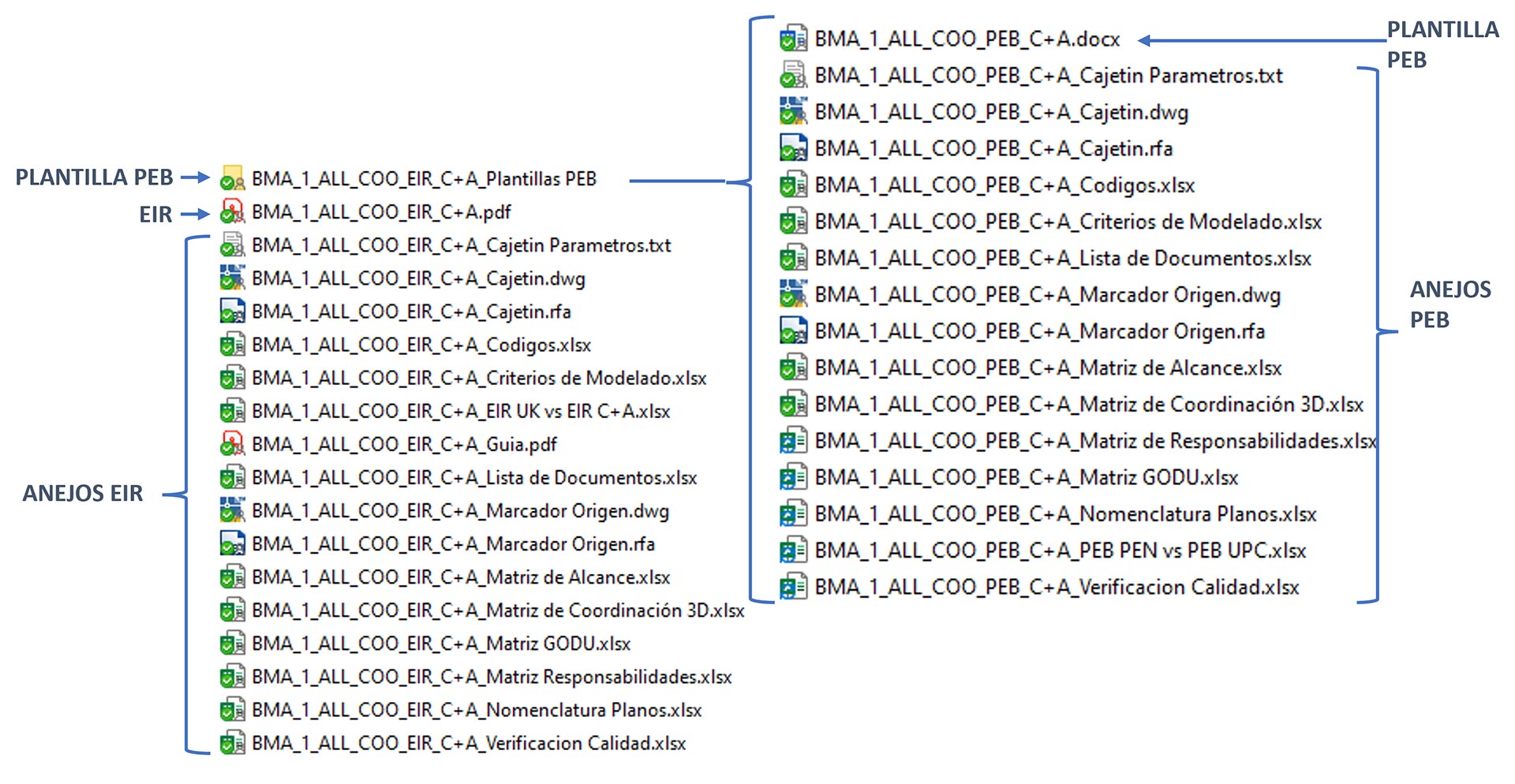

Below is an example of the contents of an EIR and its template for the BEP.

Their initial content is the same, with the difference that the former is a consultation document and the latter is a working document that may modify the provisions of the EIR in the light of any pre- or post-contractual negotiations that may take place.

In this sense, the use of this methodology during the drafting of the BEP is even more useful, since its development involves pooling requirements from various sources, they can be customers or suppliers, with different structures and levels of concreteness. During the negotiation process, the aims and objectives of all parties can be established and prioritized, and then everything else can be developed accordingly.

Concluding remarks

Defining the aims and objectives requires prior thought on the part of those involved. When it comes to EIR, this implies that an organization that intends to implement BIM in the project assignments, takes time to analyze what it really needs and why. In the case of BEP, the same thing happens, so the planning of the assignment should allow time for all parties to develop each part of it in an informed manner. Of course, knowing the purposes that motivate each objective pursued will greatly help to understand the circumstances of each party and to optimize both shared and individual efforts in the development of deliverables.

On the other hand, the structure presented here is designed as a framework that allows its contents to evolve over time. We have been implementing it for more than four years and we have not stopped introducing improvements in each new version, seeking above all to facilitate the understanding and assimilation of its contents by those involved, whether they are customers or suppliers.

For this reason, we can be sure that this is a system that works and is consistent. However, I am sure that there are other solutions that are just as valid, so your opinion is welcome.

You can find more information about this methodology and how to implement it in the “Guía para la implementación de BIM en la licitación pública”. Although focused on public procurement, its recommendations are perfectly valid in the private sector.